Photoshop isn’t the finish line, it’s just the (raster) engine

I am not only changing the way I practice and read about graphic design, but I am also rethinking the way I work with my software.

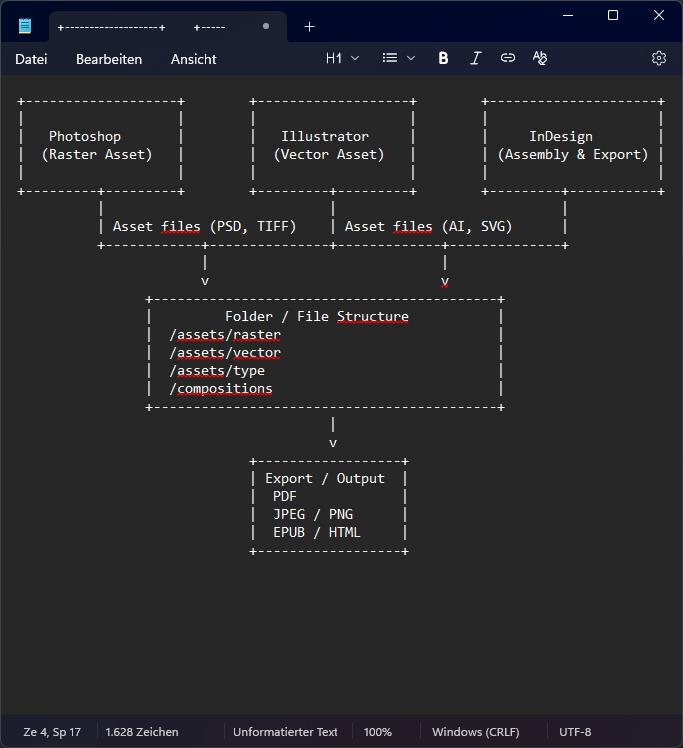

After working out my first actual social media schedule (of which this is the christening post) I realized that, despite knowing Photoshop is for raster graphics, Illustrator for vector graphics, and InDesign for composition and layout, I didn’t truly understand what that meant for my workflow.

Then along comes a neat little model by Brad Frost, called Atomic Design.

The files, layer comps, Smart Objects, AI symbols, are just assets. The finished graphic is the whole composition, not the individual pieces. InDesign, in my workflow, is where these pieces get assembled, moved around, viewed together, and iterated upon.

This, I think, is as close to a studio in silico as I dare to imagine.

Up until recently, I would put what I did in Photoshop into a folder called “Photoshop”, give the file a name prefixed by YYYYMMDD, and call it done. Same with all my other programs. Each file existed on its own, with no connection to anything–not a project, not a composition, not a larger purpose.

In a horrifying way, I was just spinning my wheels. I was using programs, but I wasn’t understanding what a finished product was.

So when I look at applying a modular system to my workflow, I no longer see what I export from Photoshop as the final product. Instead, I have assets that live inside a composition. These assets are editable, swappable, and allow iteration beyond simple versioning.

What I actually have in front of me, looks like this:

- Raster engine (pixel‑level editing, color correction, masking…)

- Vector engine (vector construction, path logic, typography geometry…)

- Compositing engine (comp/assembly, final layout, export orchestration)

So, instead of using this logic:

/illustrator

/photoshop

/indesign

I can apply this much more enticing and inspiring structure:

/assets

/raster

/vector

/type

/compositions

/exports

This already looks like a scaffold for a project, not like a graveyard full of files.

Quelle: Code & Canvas

Schreibe einen Kommentar